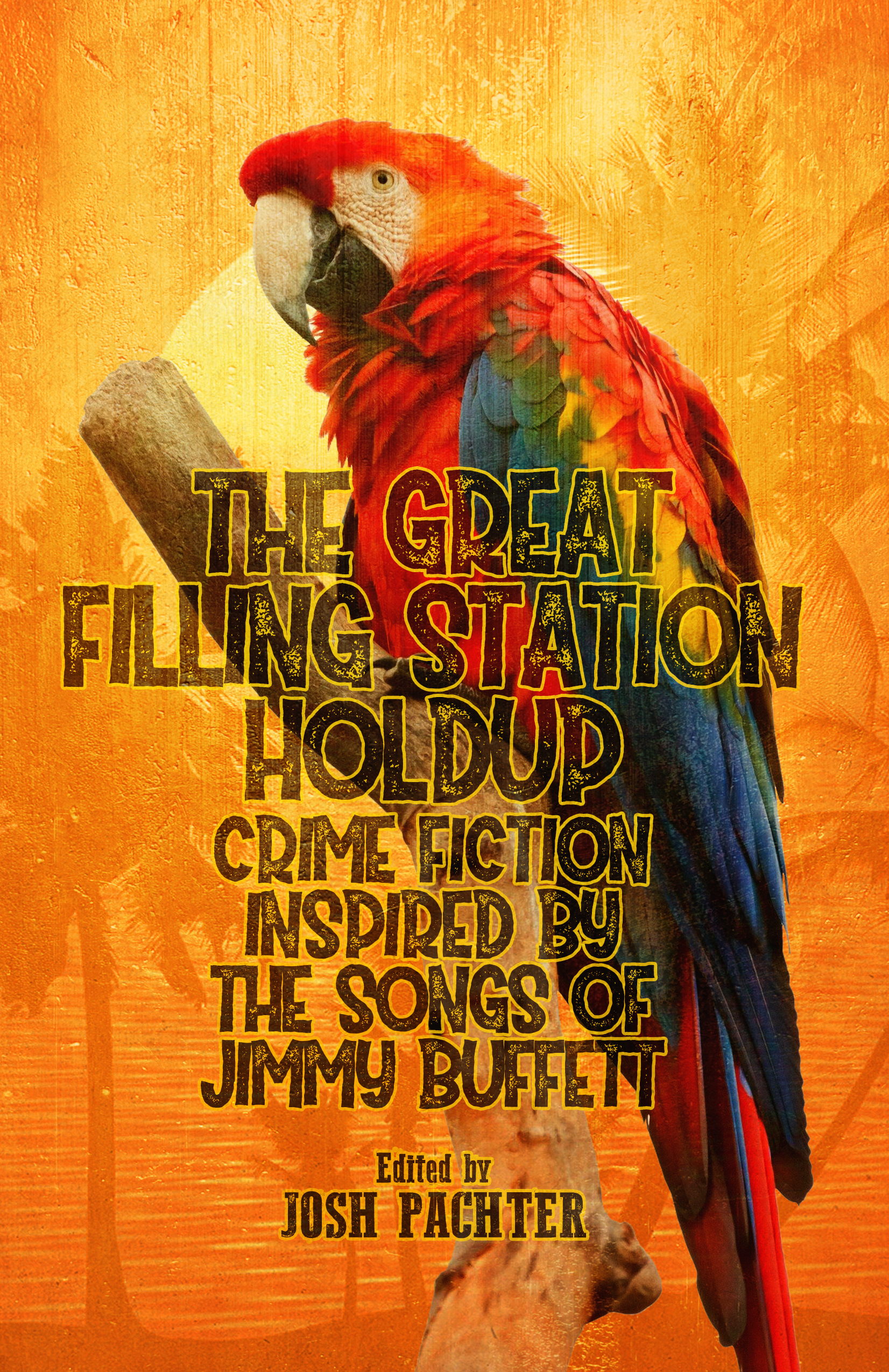

Free Short Story from Jimmy Buffet Anthology

Enjoy my free short story from the new anthology, "The Great Filling Station Hold-Up: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Songs of Jimmy Buffet," published by Down & Out Books. The other stories are as colorful as the cover.

WE ARE THE PEOPLE OUR PARENTS WARNED US ABOUT

By Elaine Viets

When I saw the letter from the CEO of Truman Auto Parts in my inbox, my heart pounded like a Chevy with a blown head gasket. What made it scary was it looked so official: heavy cream stationery, fancy logo.

Might as well get it over with, I thought. Hands trembling like a man on a three-day bender, I tore open the envelope.

“Dear Vincent Fowler,” the letter began.

Turns out it was one of those good-news/bad-news deals. The good news was I wasn’t being busted for boosting. The bad news was I was out of a job[O1] .

I’d worked for TAP for thirty years, and I admit I skimmed a bit out of the register from time to time. But, hell, they hadn’t given me a raise in a decade. Armbruster J. Truman III made thirty-two million dollars a year for manning a desk, so I figured I was entitled to a little something extra.

The company would never miss it. My store was the top-selling parts place in Humbert, Iowa, a town of fifty thousand about ninety miles south of Des Moines. I gave Truman a fair day’s work and—thanks to my initiative—went home with a fair day’s pay. Weekends, I played guitar in a Jimmy Buffet cover band at Ronnie’s Roadhouse, picked up beer money and a little more. I met my wife Sue at Ronnie’s. She was a server on the weekends, on top of her regular job at an insurance agency.

Armbruster J. the Third’s letter informed me[O2] that TAP would be closing its Humbert location in two weeks, leaving twenty-five of us unemployed. As a consolation, he promised me three thousand dollars in severance pay. Big whoop.

It was hotter than the hinges of hell when I locked up at nine-thirty that night. At home, Sue met me with a cold beer. She’s pushing forty and even prettier today than when we married ten years ago. She has big brown eyes, soft, curly brown hair, and a sexy constellation of freckles on her right shoulder. I’ve made a lot of stupid mistakes in my life, but marrying Sue was the smartest thing I’ve ever done.

She didn’t take the news I was being canned the way I’d expected.

“This is a blessing in disguise,” she said, perching on the edge of my recliner. “I’ve been dreading another Iowa winter. What would you think about moving to Florida?”

“Florida?”

“We don’t have any reason to stay here, no kids or close relatives. I’ve always wanted to live in Fort Lauderdale.”

“I like Florida,” I said. “But it’s hot there in the summer.”

She kissed my sweating forehead. “It’s been over a hundred degrees here for four days straight.”

She had me there.

“The TV weatherman fried an egg on the sidewalk on tonight’s news,” she said. “It’s going to stay this hot through September. Let’s try living in Lauderdale for a month. If we can stand the heat in August, we can stand it any time. We’ll use that three thousand dollars to relocate. What do you say?”

*

When I came home the next Monday, she said, “I found us a cute rental apartment on Coconut Isle, a man-made island off Las Olas. It’s right on a canal! We can walk to the ocean. I took it for a month.”

On Tuesday, she said, “I was talking with Betty Bradford in Muscatine. She wants to move here to spend more time with her mother. She’s always liked our house and might be interested in buying it.”

On Wednesday, Sue said, “Betty will rent our house for the month of August. If we decide to stay in Florida, she’ll buy it—furnished. We can buy all new furniture there.”

On Thursday, she said, “Nick Flynn will handle the house sale, if we go ahead with it. And he’ll only charge us half his regular fee.”

On Friday, my last day of work, Sue picked me up at the shop. The car was packed and gassed up. We cashed my final paycheck and severance check and waved good-bye to the cornfields of Iowa.

*

We enjoyed the three-day drive south, listened to Jimmy Buffet songs all the way. When we hit Fort Lauderdale, we found Coconut Isle, a well-manicured finger of land that stuck out into the Intracoastal Waterway. Number Nine, where we were staying, was a long one-story building painted bright white and trimmed in tropical turquoise. The green lawn was shaded by palm trees, and at the dock in the back bobbed a beautiful white thirty-foot Hatteras cabin cruiser. The boat’s name was lettered on the stern in gold paint: Leaky Tiki. When I saw that, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven.

Sue and I got out of the car and just stood there, admiring our surroundings: the gleaming white boat, the blue water, the rustling palm trees. It was like walking into a tourist brochure.

A guy about my age came out of the boat’s cabin with a smile on his face. “I’m Dick Puckett,” he said, and stuck out his hand for me to shake. “Are you our new tenants?”

We introduced ourselves, and Dick invited us on board for a Cajun martini. Sue’s face positively glowed. This was the life she’d dreamed about. Yes, it was hot, but there was a cool breeze off the water. And a cool drink—several of them, in fact. When Dick’s wife Kaye came home, she joined us on deck, and the four of us toasted the setting sun.

We really hit it off with our landlords. About seven o’clock, Kaye said, “I’ve got some burgers in the fridge. How about if we throw them on the grill?”

Sue went inside to help, and Gardner and I stayed on the boat, drinking martinis. He fired up the grill. Gardner was a letter carrier, and Kaye worked for the Social Security Administration.

They were generous hosts, and we had a delicious dinner of burgers, potato salad, sliced tomatoes, and chocolate cake, all the while listening to Jimmy B. tunes: “Cheeseburger in Paradise,” “Come Monday,” and Gardner’s personal favorite, “We Are the People Our Parents Warned Us About.” [O3]

As the drinks kept coming, I got my guitar from the car, and soon we were all singing along. It was midnight by the time Sue and I were ready for bed, and we were too tipsy to unload. We tottered into our new apartment and didn’t wake up until noon.

Kaye had thoughtfully stocked the kitchen with bread, butter, eggs, and coffee, and the late breakfast Sue prepared saved my hungover life.

After breakfast, I hauled our stuff out of the car, and Sue unpacked. While she settled us in, I went for a walk. The salt air was invigorating. Next door was Coconut Isle Park, a pretty pocket park with three benches and a huge ficus tree. The rest of the block was residential. The other buildings were similar to Gardner and Kaye’s: white houses with one or more rental units. About halfway down, I saw a gaunt older woman in a blue flowered housedress raking her lawn. She wore a floppy straw hat, and her strong hands were knotted with veins.

“Good afternoon,” I said.

She leaned on her rake and said, “Afternoon. And who might you be?”

“I’m Vinnie Fowler. My wife Sue and I are renting Number Nine from Gardner and Kaye Puckett.”

The woman froze. Even her frizzy gray hair didn’t move. “What do you think of them?” she asked. She sounded cautious.

“They’re terrific,” I said. “We spent the evening partying with them.”

“Humph,” she said. “Where are you and your wife from?”

“Iowa.”

“Figures,” she said. “You seem nice enough. Maybe too nice for your own good. Let me give you a word of warning: you can party on their boat as much as you want, as long as it’s at the dock, but don’t ever go on a cruise with them. The last fella did that, he never came back. He was from Michigan.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Why didn’t he come back? Or why was he from Michigan? I can’t answer that last question, but as to why he didn’t come back, my guess is he crossed those two somehow and they tossed him overboard. The crabs got to his body, and there wasn’t much left. Look it up. His name was Everding. Elmore Everding. It was in the papers.”

Suddenly, despite the August sun, I felt cold.

“Uh, thank you,” I said, backing away.

“You’re welcome,” she said. “He was a nice friendly guy like you before he became fish food.”

I waved good-bye and noticed the woman had two rental units behind her house. I tried to tell myself she was a competitor of Kaye and Gardner’s, but I didn’t quite believe it.

Back at our place, Sue was so happy I thought she’d bust. I didn’t say anything about the conversation I’d had on my walk, but a thought gnawed at me: how could Gardner and Kaye afford this big house and that fine boat on two government salaries? The taxes and upkeep alone ought to have wiped out their paychecks.

As the month rolled on, our money disappeared at an alarming rate. Sue found a part-time job as a waitress, and I went to work at a hardware store. We agreed that we weren’t going back to Iowa.

One night after dinner, we found our ideal house: a two-bedroom Caribbean cottage with—I swear—a white picket fence. I’m about the last guy who ever thought he’d want a house with a picket fence, but Sue fell in love with the place, and I had to admit it was pretty. It was painted a soft yellow with white trim, set on a little canal, with a big mango tree in the yard.

“We can pick our own mangoes and have them for breakfast,” Sue said.

The house was for sale at what in Fort Lauderdale was a bargain price, but a Fort Lauderdale bargain was not the same as an Iowa bargain. If Betty bought our house in Humbert, we’d clear enough for the down payment, but I had no idea how we could keep up with the mortgage when our new jobs paid so little.

“Maybe Gardner and Kaye have some ideas,” Sue said. “You could ask him.”

Asking people about their finances is pretty personal, so I held off until one night at a cookout, when Gardner was pretty well oiled. After we finished the best barbecued ribs I’d had in a long time, Gardner and I offered to help do the dishes, but the ladies said they had it under control and shooed us out of the kitchen. Personally, I think they wanted some girl talk.

So Gardner mixed another batch of martinis, and we sat on the deck of his boat. A light breeze kept the mosquitoes away.

“Gardner,” I said, “I’ve got to hand it to you. You and Kaye manage to live like kings on a couple of civil servants’ salaries. How do you do it?”

Gardner’s slightly bloodshot eyes shifted from the cabin cruiser to the house and rental unit, then to the whispering palm trees.

“Well, Vinnie, I guess I’m just one lucky SOB. Kaye inherited the house and the rental unit from her father when he died in 1997. The rental gives us a nice little cash boost. You know that.”

Boy, did we ever. We were paying two thousand a month for a one-bedroom in the off-season. During the winter months, when the snowbirds came to town, the rent went up to three grand.

“As for the boat, we got that after Hurricane Wilma. It was damaged—we picked it up cheap—and I restored it. What you’re looking at is the result of many nights and weekends of hard labor.” He waved his martini glass at the nautical-themed pillows and upholstery and the shining mahogany deck.

That all made sense, I guess, but not quite. I had the odd feeling my new friend was holding something back.

Then again, so was I. I didn’t mention Elmore Everding.

That night in bed with Sue, I told her what I’d learned.

“Hard to believe,” Sue said.

“I agree.”

“Gardner and Kaye live in one of the richest sections of Fort Lauderdale, and this property needs constant upkeep. Kaye said they’re going to have the house painted next month. And I won’t begin to guess what their taxes are. I guess they’re better at managing money than us.”

I wasn’t convinced. But Sue, who always has a plan for everything, said, “I think we should start saving our change. I get a lot of tips, and they add up.”

“We’re going to pay the mortgage in quarters?”

“You can laugh, but it was my tip money that paid for gas and meals on the trip down here.”

Now I’d hurt her feelings. I felt like a rat. “You’re right, honey,” I said. I kissed her, and she kissed me back, and soon we forgot all about how Kaye and Gardner made their money.

Our idyllic month was nearly at an end. Sue was in love with Florida and wouldn’t hear a word against it—she even claimed to like the humidity. “It’s good for your skin,” she said.

I continued to worry about our landlords, but I said nothing to my wife. We had dinner with Gardner and Kaye almost every night, and they were fun to be with—kind and witty and always entertaining.

We still hadn’t figured out how we would buy our dream cottage, but Sue was optimistic. “Something will happen,” she said. “I just feel it.”

I felt something, too, but it was an ominous heaviness in the pit of my stomach.

One afternoon—the last of the month we’d paid for—I came back from the hardware store and found Sue pacing in the driveway. As I pulled in, I saw she was white-faced and shaking. She practically dragged me out of the car.

“Honey, what’s wrong?”

“Look in the mailbox!” she said.

At the end of the drive was a plain black mailbox mounted on a black metal post.

“Betty promised to send me an offer on our house. I checked the mail, and you won’t believe what’s in there! Look!”

I pulled open the box, and stuffed inside was a one-gallon plastic freezer bag fat with what I believe the police call a “green leafy substance.” In other words, pot. Nearly four pounds of it, by my estimate.

“That’s how Kaye and Gardner can afford all this,” Sue said. “They’re drug dealers! What are we gonna do?”

I put my arms around her. “We’re not going to do anything. We leave tomorrow morning. We’ll stay at the Residence Inn until we find a more permanent place.”

“But they’re having a good-bye party for us tonight. I can’t go. I can’t look at them after this.”

She started crying. I hugged her and patted her slightly sweaty back.

While I did, I formulated a plan. Sue had been right. Something would happen, she’d said, and it certainly had—and we could use it.

I whipped out my cell phone and took pictures of the mailbox and its contents. “Are you sure you put the bag back exactly the way it was?”

“Yes! No! I don’t know.”

I guess you’re wondering why Sue was making such a big deal over a package of pot. Well, neither one of us is an angel, but we don’t use illegal drugs. We don’t judge people who like their weed, it’s just not our thing. And we had never encountered a dealer before.

“You don’t have to go to the party,” I said. “I’ll tell Gardner and Kaye you ate some bad fish for lunch and have an upset stomach. You go inside and close the curtains and get some rest. I’ll handle this.”

I checked online and found a website, FreeAdviceLegal, that said possession of marijuana is generally illegal in Florida. Medical marijuana seemed to be permitted for personal use, but you had to have a “debilitating medical condition,” which included things like cancer, epilepsy, and multiple sclerosis. So far as I knew, Gardner and Kaye were healthy as horses, and the law defined personal use as twenty grams or less—not four pounds.

Another piece of free advice caught my eye: “You do not have to be caught in the act of selling marijuana to be charged with attempted distribution.” Possession of twenty-five pounds of pot or less within a thousand feet of a park or school was a felony with a maximum of fifteen years in prison and a ten-thousand-dollar fine.

Next I searched for information on the late Elmore Everding. A headline said, “Suspected Drug Dealer Found Dead in Fort Lauderdale Canal.” The article was short: “The badly decomposed body of Elmore Everding, 37, was found in a canal off Las Olas Boulevard today. Mr. Everding, a former resident of Addison, Michigan, lived on SW 13th Street in Fort Lauderdale. Police sources say he was a low-level drug dealer and may have been involved in a territorial dispute over drugs. Police say Mr. Everding was struck on the back of the head and fell or was thrown into the water. Results of the autopsy are pending.”

Was Elmore trying to break into Kaye and Gardner’s business—if they had a business? Or did they abruptly terminate a partnership with him? I’d find out tonight, I thought.

Meanwhile, I needed evidence. I made sure my cell phone was charged, grabbed a bottle of water, and walked to the pocket park next door. At five-thirty, the hot afternoon was starting to cool off. I sat on the bench beneath the ficus tree, where I had a clear view of the Pucketts’ mailbox. I set my camera on video mode. Fifteen minutes later, a red BMW pulled up. A man in a business suit got out, opened the mailbox, took out the bag of pot, and left a thick manila envelope in its place.

I made sure I got several good shots of the car’s license plate as it drove off. Two minutes later, Kaye came out of the house like a shot. She opened the mailbox and grabbed the envelope. It slipped out of her hands and fell to the concrete driveway, where it burst open. Money spilled out, a lot of it. Kaye scooped it up and hurried back inside.

I got the whole thing on video. Gardner might not care about himself, but he’d do whatever he had to to protect Kaye.

I called our friend Nick in Iowa, asked if I could email him some notes and a video file, and[O4] made him promise not to open the message unless he hadn’t heard from me within the next two days.

“Everything okay down there, buddy?”

“Fine,” I said. “This is just a little insurance. We may never need it.”

But I did need a weapon. Though we usually drank Cajun martinis at Kaye and Gardner’s, tonight I’d switch to beer. If I knocked the neck off a bottle … well, I’d seen enough bar fights at Ronnie’s Roadhouse, I knew the damage a broken beer bottle could do.

I went into our apartment to get my wallet.

“Where are you going, honey?” Sue asked.

“Thought I’d pick up some beer,” I said.

“Take my quarters,” she said. “I have four rolls on the dresser.”

I bagged the rolls in a clean black sock and stuck it in my pocket.

At the supermarket, I bought a six-pack of Heineken[O5] . By the time I got to Kaye and Gardner’s with a fake smile plastered on my face, it was five to seven.

“Hey, hey,” Kaye said. “Where’s your better half?”

“She’s not feeling well,” I said. “She ate some bad fish for lunch.”

“That’s a shame,” Kaye said.

“Hope she’s better soon,” Gardner said. “You switching to beer?”

“Just had a taste for it.”

“It’s warm,” he said. “Let me put it in the cooler. Meanwhile, have a martini.”

He handed me a frosty one in a plastic cup—Gardner didn’t like glass on his boat—and I pretended to sip it.

Kaye stood up and said, “I have some things to finish in the kitchen. I’ll let you boys talk.”

As she sashayed toward the house, Gardner said, “How was your last day? Anything unusual happen?”

“Nope,” I said. “Just another day in Paradise.”

“What about your little kerfuffle at the mailbox?” he said, with a big Cheshire-cat grin.

“What—?”

“Don’t bother to deny it,” Gardner said. “I have cameras everywhere.”

Of course he did. I looked around and saw the red lights, like demons’ eyes, winking from the deck, the covered patio, the palm trees, and by the mailbox at the end of the drive. I cursed myself for getting soft, now that we’d moved to the tropics. I was used to working with cameras: they had[O6] them all over the parts store back in Humbert. I’d personally disabled the one by the register, and the cheapskates had never fixed it. Hah! That had cost them a pretty penny.

But now my carelessness was going to cost me my life.

“I saw the way your wife reacted to that bag of mulch in the mailbox[O7] .” Gardner laughed.

“That wasn’t mulch,” I said.

“It’ll look like mulch in the photo you took with your cell phone.”

“Maybe, but what about the green stuff that landed all over your driveway when Kaye dropped the envelope? I got that on camera, too—and your customer’s plate.”

Gardner looked surprised, but he recovered quickly. “Well, I’ve got your wife,” he said. He fished a key out of his pocket, and I looked into his slitty mean eyes. “By now, Kaye’s bolted the doors to your unit from the outside. We have the only two keys. So what do you say you and me go for a cruise and have a little talk?”

I remembered what the woman up the street had warned me: don’t go out on Gardner’s boat.

“I get seasick,” I said. “I’m from Iowa. Biggest body of water I like is a bathtub. That’s why I didn’t sign up for the Naval Academy, like my parents wanted.”

“If you ever want to see your wife again, you’ll go for a ride,” he said. He had a gun in his hand, and he handled it like he knew how to use it.

I tried to look brave. “Can I have a beer now?”

“No. Sit down and shut up.” He jabbed me in the back with the gun, and I sat.

“Don’t even think about leaving,” he said, “or your wife will die.”

He went into the cabin to start the engine, and I looked around frantically for a weapon. I could hit him with a deck chair. But he had a gun.

I slapped my pockets, checking for my car keys. I could poke him in the eye with a key—but he had a gun.

Wait a minute. Sue’s quarters. I’d paid for the beer with a credit card, so they were still in my pocket. Four rolls of quarters in a sock would make a powerful weapon.

I splashed the rest of my martini on the deck. The engine sputtered to life, and Gardner reappeared.

“Hey!” he said, slipping on the puddle of martini. I walloped him good and hard with the sock full of quarters, and he went down like a sack of feed. I took his gun away and killed the engine. Then I opened myself a beer and sat there with his gun, waiting for him to wake up.

“What happened?” he moaned at last. Then he saw the gun in my hand. “You son of a bitch!”

“That’s no way to talk about your new partner,” I said. “Now here’s how this going to work. I emailed the video I shot of Kaye[O8] to my lawyer in Iowa, and if he doesn’t hear from me, he’ll send it to the Fort Lauderdale police and the DEA. You’re looking at fifteen years and a ten-thousand-dollar fine, Gardner, plus extra time since you’ve been dealing drugs within a thousand feet of a park. Oh, and using a mailbox as a drug drop, that’s a federal crime. I’m surprised a mail carrier didn’t know that.”

He rubbed his head and tried to sit up. “What do you want?”

“I want fifty percent of your gross.”

“Thirty,” he said.

“You really want to bargain with Kaye’s freedom? Fifty.”

“Okay,” he said.

“No tricks, now. Remember, if anything happens to me, my lawyer will send that incriminating video to the cops, along with a suggestion they check this boat for Elmore Everding’s DNA. He had a head wound, so he must have done some bleeding. A little Luminol will light that blood right up, no matter how many times you washed the deck. Now give me that key, and I’ll let my wife out.”

I tossed his gun in the water, locked him in the cabin and set Sue free. She was already packed. We loaded our car and headed for the Residence Inn.

Sue and I kept our jobs. I got promoted to full-time at the hardware store, and she was soon working fifty hours a week at the restaurant. Our bosses loved what they called our “Midwest work ethic,” which in South Florida meant we showed up on time. We sold our house in Humbert to Betty and used the proceeds as a down payment on our dream cottage.

Sue and I never barbecued with Gardner and Kaye again, and we both felt bad about that. But not too bad. The money was rolling in. Gardner had a good situation. He sold pot to the people who sold pot to the young professionals downtown, nice white folks who smoked a little weed in their homes.

I promised Gardner that[O9] as soon as we paid off the mortgage on the cottage and had a hundred-thousand-dollar nest egg, I’d dissolve our partnership and destroy the video of his wife. He wants rid of me, so I figure we should reach that benchmark in a year or two. Meanwhile, I check in with Nick once a week, just for insurance.

Eventually, Florida will legalize marijuana, and then there’ll be no need for people like Gardner and me.

But in the meantime, well, we are the people our parents warned us about.